The Reliability of the New Testament Documents

Manuscript Evidence

Historians who study the New Testament (NT historians) approach it as they would any other ancient work, not as sacred scripture. When compared to other ancient texts, the manuscript evidence for the New Testament is exceptionally strong.

Quantity of Manuscripts: We have over 5,600 complete or fragmented Greek manuscripts, 10,000 Latin manuscripts, and 9,300 manuscripts in other ancient languages (Syriac, Slavic, Gothic, Ethiopic, Coptic, and Armenian).

Date of Manuscripts: These manuscripts date from as early as c. 125 AD (the John Rylands papyrus, our oldest copy of John's fragments) to the 15th century.

Patristic Quotations: The early church fathers quoted the New Testament so extensively that much of it could be reconstructed just from their writings.

Accuracy: NT historians agree that our copy of the New Testament is at least 97% accurate compared to the original autographs. The remaining 3% consists of minor variants that do not affect any core doctrine.

By contrast, the ancient work with the next highest number of copies is Homer's Iliad, with only 650 manuscripts.

Author | Date Written | Earliest Copy | Time Span | Copies | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lucretius | died 55 or 53 B.C. | --- | 1100 yrs | 2 | --- |

Pliny | A.D. 61-113 | A.D. 850 | 750 yrs | 7 | --- |

Plato | 427-347 B.C. | A.D. 900 | 1200 yrs | 7 | --- |

Demosthenes | 4th Cent. B.C. | A.D. 1100 | 800 yrs | 8 | --- |

Herodotus | 480-425 B.C. | A.D. 900 | 1300 yrs | 8 | --- |

Suetonius | A.D. 75-160 | A.D. 950 | 800 yrs | 8 | --- |

Thucydides | 460-400 B.C. | A.D. 900 | 1300 yrs | 8 | --- |

Euripides | 480-406 B.C. | A.D. 1100 | 1300 yrs | 9 | --- |

Aristophanes | 450-385 B.C. | A.D. 900 | 1200 yrs | 10 | --- |

Caesar | 100-44 B.C. | A.D. 900 | 1000 yrs | 10 | --- |

Livy | 59 B.C. - A.D. 17 | --- | ??? | 20 | --- |

Tacitus | circa A.D. 100 | A.D. 1100 | 1000 yrs | 20 | --- |

Aristotle | 384-322 B.C. | A.D. 1100 | 1400 yrs | 49 | --- |

Sophocles | 496-406 B.C. | A.D. 1000 | 1400 yrs | 193 | --- |

Homer (Iliad) | 900 B.C. | 400 B.C. | 500 yrs | 643 | 95% |

New Testament | 1st Cent. A.D. (50-100) | 2nd Cent. A.D. (c. 130) | < 100 years | 5600 | 99.5% |

Important Manuscript Papyri | Contents | Date Original Written | MSS Date | Approx. Time Span | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

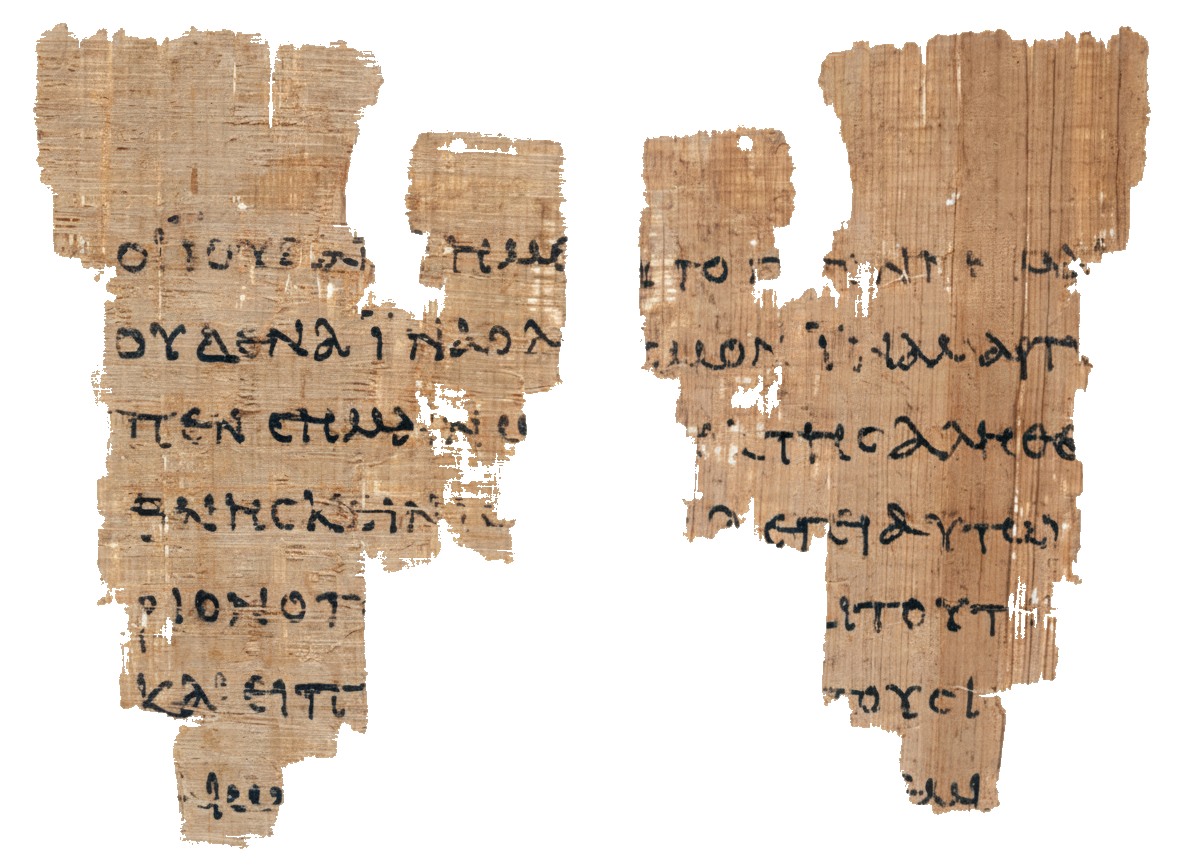

p52 (John Rylands Fragment) | John 18:31-33, 37-38 | circa A.D. 96 | circa A.D. 125 | 29 yrs | John Rylands Library, Manchester, England |

p46 (Chester Beatty Papyrus) | Rom. 5:17-6:3, 5-14; 8:15-25, 27-35; 10:1-11, 22, 24-33, 35; 16:1-23, 25-27; Heb.; 1 & 2 Cor., Eph., Gal., Phil., Col.; 1 Thess. 1:1, 9-10; 2:1-3; 5:5-9, 23-28 | 50's-70's | circa A.D. 200 | Approx. 150 yrs | Chester Beatty Museum, Dublin & Ann Arbor, Michigan, University of Michigan library |

p66 (Bodmer Papyrus) | John 1:1-6:11, 35-14:26; fragment of 14:29-21:9 | 70's | circa A.D. 200 | Approx. 130 yrs | Cologne, Geneva |

p67 | Matt. 3:9,15; 5:20-22, 25-28 | circa A.D. 200 | Approx. 130 yrs | Barcelona, Fundacion San Lucas Evangelista, P. Barc. 1 |

p52 (John Rylands Fragment) John 18:31-33, 37-38

Internal Evidence: Early Recognition as Scripture

The New Testament writers themselves recognized each other's writings as Scripture, on par with the Old Testament.

Here, Paul quotes both Deuteronomy and Luke's Gospel, calling both "Scripture":

Deuteronomy 25:4: Do not muzzle an ox while it is treading out the grain.

Luke 10:7: ...for the worker deserves his wages.

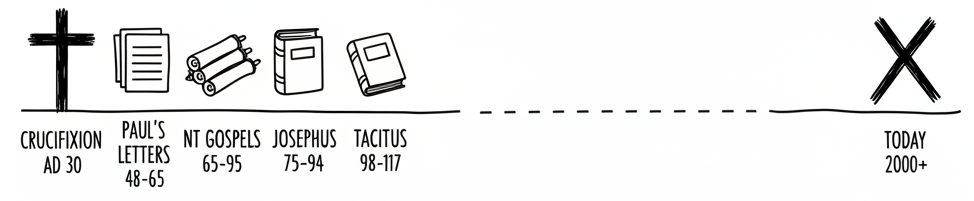

Early Dating of the Gospels

The Gospels were written within a few decades of the events they describe, which is remarkably early for ancient historical documents.

Roman historian Colin Hemer argues for an early date by reasoning backward from the Book of Acts.

Acts records the martyrdoms of Stephen (Acts 7:54-60) and James (Acts 12:1-2).

However, it fails to mention the later, more significant deaths of Peter and Paul (c. 63-66 AD), the Jewish war with Rome (66 AD), or the destruction of Jerusalem (70 AD).

Acts ends abruptly with Paul under arrest in Rome, with no resolution.

The most reasonable explanation is that Luke wrote Acts before these events occurred, around 62 AD. Since Luke wrote his Gospel before Acts, and Matthew and Mark likely preceded Luke, the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) were written before the mid-60s AD.

By contrast, the earliest biographies of Alexander the Great were written nearly 400 years after his death.

Authorial Intent: Writing Accurate History

The Gospel writers explicitly state their intention to write historically accurate accounts, not fiction.

Luke's Preface

Luke's introduction is a single, carefully constructed sentence in the style of the finest Greek historians like Thucydides, Philo, and Josephus. By using the classical Greek word epeideper ("inasmuch as") and detailing his research methods, Luke assures the reader of his capability, thorough research, and reliability.

Undesigned Coincidences

An undesigned coincidence is when one account provides unexplained details that are incidentally clarified by another account.

Example: Why Ask Philip?

John 6:5-6: When Jesus looked up and saw a great crowd coming toward him, he said to Philip, "Where shall we buy bread for these people to eat?" He asked this only to test him, for he already had in mind what he was going to do.

Luke 9:10: When the apostles returned, they reported to Jesus what they had done. Then he took them with him and they withdrew by themselves to a town called Bethsaida.

John doesn't explain why Jesus directed his question to Philip. Luke, in a different context, mentions the feeding of the five thousand took place near Bethsaida. The connection is made clear when we read another passage in John:

John 1:44: Philip, like Andrew and Peter, was from the town of Bethsaida.

Jesus asked Philip, the local, where to buy bread. This casual, interlocking detail across different Gospels points to authentic, eyewitness-based accounts.

Gospel Writers' Intentions

The Gospel writers prioritized historical accuracy, though they sometimes reordered events or summarized sayings for thematic purposes.

Order of Events: The Temptation of Jesus

Matthew and Luke record the same three temptations but in a different order, indicating they arranged them for theological emphasis rather than strict chronology.

Matthew 4:1-11 | Luke 4:1-13 |

|---|---|

1. Stones to bread (vv. 3-4) | 1. Stones to bread (vv. 3-4) |

2. Jump from temple (vv. 5-7) | 2. Kingdoms of the world (vv. 5-8) |

3. Kingdoms of the world (vv. 8-9) | 3. Jump from temple (vv. 9-12) |

The Gist of Jesus' Sayings

The Gospels often record the "gist" or summary of what Jesus said, rather than a verbatim transcript. The core message is identical, even if the exact wording differs.

The Father's Voice at Baptism:

Matthew 3:17: This (G3778 – οὗτος) is (G2076 – ἐστίν) my beloved Son, in whom (G3739 – ὅν) I am well pleased.

God speaks about Jesus in the third person (“This is… in whom…”).

Mark 1:11: Thou (G4771 – σὺ) art (G1488 – εἶ) my beloved Son, in thee (G4671 – σοί) I am well pleased.

God speaks directly to Jesus in the second person (“You are… in you…”).

Luke 3:22: (Same as Mark 1:11) Thou (G4771 – σὺ) art (G1488 – εἶ) my beloved Son, in thee (G4671 – σοί) I am well pleased.

Identical to Mark—God speaks directly to Jesus in the second person.

Peter's Confession:

Matthew 16:16: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.”

Mark 8:29: “You are the Christ.”

Luke 9:20: “The Christ of God.”

The Last Supper

The accounts of the Last Supper in the Gospels and 1 Corinthians show a similar pattern of summarizing the event while preserving the essential words and actions of Jesus.

1 Corinthians 11:23-26: For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body, which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also he took the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord's death until he comes.

Luke 22:19-20: And he took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it and gave to them, saying, “This is my body, which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” And likewise the cup after they had eaten, saying, “This cup that is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood.”

Matthew 26:26-29: Now as they were eating, Jesus took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to the disciples, and said, “Take, eat; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, saying, “Drink of it, all of you, for this is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins...”

Mark 14:22-25: And as they were eating, he took bread, and after blessing it broke it and gave it to them, and said, “Take; this is my body.” And he took a cup, and when he had given thanks he gave it to them, and they all drank of it. And he said to them, “This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many...”

Ipsissima Verba vs. Ipsissima Vox

Historians distinguish between ipsissima verba ("the exact words") and ipsissima vox ("the exact voice" or gist). An accurate summary of a teaching is just as historical as a verbatim quote. The Gospel writers used both methods. The trustworthiness of these summaries is supported by the character of the writers and the presence of eyewitnesses (both friendly and hostile) who could have challenged a fabricated report.

Case Study: Mary at the Tomb

Matthew, Mark, and Luke report that a group of women went to the tomb.

John focuses on Mary Magdalene. In John 20:1, she appears to go alone.

However, in the next verse (John 20:2), she tells the disciples, “They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we do not know where they have laid him.”

John's focus on Mary doesn't contradict the other Gospels. Her use of "we" indicates others were with her, and she was speaking for the group. This is a common feature of ancient storytelling, where one individual's story represents the group's experience.

Authenticity of Names and Eyewitness Testimony

The use of personal names in the Gospels provides strong evidence that they are based on eyewitness accounts from first-century Palestine.

Name Frequency

The statistical distribution of personal names in the Gospels aligns perfectly with the known popularity of names in first-century Palestine, but not with naming patterns in other regions or later periods.

Data from Lexicon of Jewish Names in Late Antiquity:

Men: 41.5% of Palestinian Jewish men bore one of the nine most popular names (Simon and Joseph being the top two). In the Gospels and Acts, this figure is 40.3%.

Women: 49.7% of Palestinian Jewish women bore one of the nine most popular names (Mary and Salome being the top two). In the Gospels and Acts, this figure is an even more concentrated 61.1%.

This specific naming pattern could not have been invented by writers outside of first-century Palestine.

Popularity of Hasmonean Names

Why were certain names so popular? Six of the nine most popular male names (John, Simon, Judas, Eleazar, Jonathan, Mattathias) and the most popular female names (Mary/Mariam, Salome) were associated with the Hasmonean dynasty, the last independent Jewish rulers. The use of these names was likely a patriotic gesture during the period of Roman rule.

Naming Conventions Indicate Eyewitness Sources

The Gospels often name minor characters who are not central to the story. Bauckham argues these individuals were likely the eyewitness sources for the accounts in which they appear.

Beneficiaries of Miracles: While most are anonymous, some are named, such as Jairus (Mark/Luke), Bartimaeus (Mark), and Lazarus (John).

Other Minor Characters: Why name Simon the Pharisee (Luke 7) or Simon of Cyrene? Why name Cleopas on the road to Emmaus (Luke 24:18) but not his companion? The most plausible reason is that these were the people who originally told the stories.

Protective Anonymity

In some cases, a person who is anonymous in Mark's Gospel is named in a later Gospel, like John. This may have been to protect the person's identity when the initial account was written.

The Woman Who Anointed Jesus: Mark's Gospel promises her story will be told forever but leaves her anonymous (Mark 14:3-9). John, writing later, identifies her as Mary of Bethany. Anointing Jesus as "Messiah" (Anointed One) was a politically dangerous act, and naming her could have put her at risk.

The High Priest's Slave: Mark mentions the slave whose ear was cut off but doesn't name the attacker or the slave. John identifies them as Peter and Malchus.

The Inclusio of Peter in Mark's Gospel

An inclusio is a literary device where a section is framed by similar material at the beginning and end. Mark's Gospel appears to use Peter as an inclusio, suggesting he is the primary eyewitness source.

Beginning: The Gospel begins with Jesus calling Peter (Mark 1:16).

End: The angel at the tomb instructs the women to "go, tell his disciples and Peter " (Mark 16:7).

This bracketing of the narrative points to Peter as the authority behind Mark's account.

The Burden of Proof: Why Trust the Gospels?

A common question is, "How can we trust documents written two thousand years ago?" This concern raises the issue of the burden of proof. Should we assume the Gospels are unreliable unless proven reliable (guilty until proven innocent), or should we grant them the same trust we give other historical documents (innocent until proven guilty)? The skeptical assumption is unwarranted for several key reasons.

1. Insufficient Time for Legendary Corruption

The crucial time gap is not between the evidence and today, but between the events themselves and the writing of the evidence. The Gospels were written and circulated within the lifetimes of eyewitnesses—both friendly and hostile—who could have corrected or challenged fabricated stories. This historical proximity is vital because it leaves insufficient time for legendary influences to erase the core historical facts.

2. The Gospels Are Not Myths or Folktales

The Gospel narratives are not analogous to folk tales, myths, or urban legends. Unlike myths, the Gospels are grounded in real history, featuring verifiable people, places, and events. Figures like Pontius Pilate, Caiaphas, and John the Baptist are not fictional characters; their existence is corroborated by external sources, including the first-century Jewish historian Josephus.

3. Reliable Oral Tradition

In the oral culture of first-century Israel, the ability to memorize and faithfully transmit large amounts of information was a highly developed and prized skill. From a young age, children were trained in the home, school, and synagogue to memorize sacred tradition with great accuracy. The disciples would have applied this same care to preserving the teachings of Jesus. Therefore, comparing the transmission of these sacred accounts to the children's game of "Telephone" is a gross misrepresentation of the cultural context.